As we enter Holy Week, we approach the end of Lent. I have not always been a fan of the liturgical calendar, but it is slowly growing on me. I think it has something to do with getting older, years blending, and time (age) being less important. For me this blending comes with a sort of nostalgia for the repetitions of existence. Maybe it was just the circles I am traveling in this year, but Lent took on new potency. In a large part because of the “hit” of Atheism for Lent, as it shed some alternative perspectives on what Lent might look like for individuals.

I am not

very good at giving things up for Lent, nor have I found doing so to be a formative experience. Therefore,

this year, rather than giving up something, I decided to intentionally reflect.

I was not sure what that might look like at the beginning. But as Lent progressed,

I found myself thinking a lot about the void, nihilism, and the abyss. This is

not an uncommon state of reflection for me, nor was it disconnected from my academic

studies. I read Feuerbach’s “The Essence of Christianity” for class, in which

he argues all of Christianity is just projection of Man onto the Heavens. This can

be troubling for some to view their beliefs as nothing more than projections of

themselves, yet for me it was a devotional endeavour. Examining

beliefs, finding myself within them, analyzing what might be me, what might be “other”

than me, was an interesting process. In this reflective state, there is a lot

of time to view one’s own evil, sin, loss, failure (whatever you want to call

it). This posture leads back to my own emptiness, the hollow shell of

life, the meaninglessness of existence, and often the pervasive experience of

the absence of God.

When I

stare into the void, I am either wooed in, or propelled outwards. The abyss has

the ability to offer a strange sense of solace, in the absence of all there is

deep calm. OR, my surroundings propel me back into the sensual reality around

me. The necessity of food, life, light, routine all act as forces pulling me

back into space and time. It is a dance, to and fro.

These

reflections were furthered by Kierkegaard’s book, “The Sickness unto

Death.” In which he argues that the self’s relation to itself, by necessity,

must be realized through an external third. Thus, everyone is in despair if

that third is not God. Yet even if you think you are relating to God, you are

probably not, because it might be your own piety, or any number of Idols you

think are God, but will in fact be revealed to not be God. (Peter Rollin’s new

book “Idolatry of God” explores some ways of thinking about this; considering that God is

often an idol of certainty and satisfaction, not in fact God). In this, the

void is ever present; it is just beneath the surface of the things that pull

away from the void. Beneath the joy of one moment is the emptiness of the next.

The

final part of my reflection was writing the paper I posted two weeks ago, “Is Evangelicalism Worth a Bailout.” In which I consider the intersection of

Capitalism, atonement theory, the rise of Evangelicalism, and environmentalism. While dwelling upon this topic, I was once again confronted by the horrors of

human action, the stark depravity of the systems we have created, the rape of

Mother Earth, and the blame we all must own due to our complacency with such

systems.

It was a

Lent full of lament.

I often

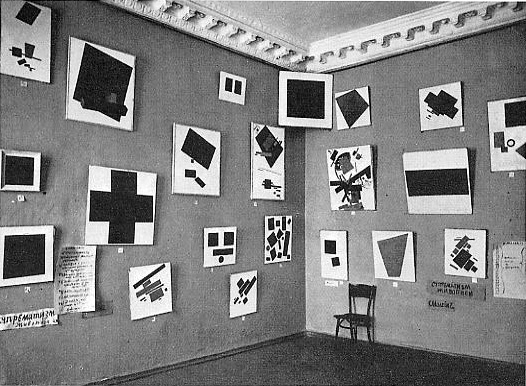

find myself thinking in images. As I was considering the world, reflecting upon

Lent, and the death of Jesus, I was drawn back to two of my favourite artists.

First, Kazimir Malevich, who confronting despair, anxiety, and life reduced

things to geometric shapes. (See Black Square, my first interaction with

Malevich).

The

second artist is Emily Carr, which is probably due to living in Vancouver. One

of her paintings is probably my favourite rendition of the crucifixion. The

three trees remain after a clear cut. They draw the viewer into the heavens. The painting confronts one with the horror and ecological destruction of clear

cutting the magnificent old-growth forests of BC. Simultaneously, however, the viewer is being

drawn out of one’s horror and into the light.

I took

some time this reading break to work on a project of depicting my Lenten

reflections by bringing together these two artists. I painted a crucifixion scene. It is a grey cityscape,

which doubles as a Malevich inspired Cross. I think the rest is self-explanatory.

I have found it helpful as an Icon leading me into the despair of the cross. In

the spirit of Atheism for Lent, I encourage you to use it as an Icon of despair

this Holy Week. As we move towards Friday, try to experience it without the knowledge that Sunday is

coming. Experience the week as if Friday is the END.

42.23.34:

“Jesus said, ‘Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.’”

I would

love to know your thoughts, questions, comments, and emotions, regarding this

piece or anything I wrote.

Hey Silas,

ReplyDeleteIt's Robert, Dennis Rempel's friend. Thanks for this post. I am studying Kierkegaard at school now and I really appreciate the chance to interact with someone who understands him and takes him seriously in real life. You offer some truly profound reflections and suggestions. In reaction, I think I might have the same reservations as Kierkegaard to exploring despair for devotional reasons, even coming up to good Friday. Every moment of despair is, by his definitions, a perpetuation of sin. To not relate infinitely to God and rest in him as infinite possibility is the self's defiance or weakness, the point at which it refuses to submit to its originator. The type of reflection in this post is so insightful because it enables us to recognize when we are in such a state, but I think the proper response to such recognition is never to perpetuate or explore that despair, but to relate with true faith to God.

By the way, if you are interested there is a professor who just finished his PHD on Kierkegaard giving a lecture on 'Kierkegaard on hope' at UFV this week. It is 4:30-6:00 on Thursday in room A225.

Thanks for interacting Robert,

ReplyDeleteI have a few thoughts about your comment. I think you are correct that Kierkegaard would be on the same page as yourself in an aversion to engaging despair for devotional reasons, but I am not. I mention the Idolatry of God, I think you can also have an idolatry of resting in a God of “infinite possibility.” To this I might say: Sin, sin boldly! Rather than hiding our idolatry this week, idolatry of certainty, or idolatry that we know what relating to God in true faith is.

If you do not want to sin boldly, and think you are in properly relating to yourself in relation to God, you can still partake in a form of despair this week. My understanding of Kierkegaard is that when he speaks of despair there must be two things going on. We might call them relational despair and emotional despair. What I think Kierkegaard is talking about in “The Sickness Unto Death” is relational despair. Despairing in one’s relationship to oneself, which he argues is due to improperly relating to God. This is what he calls sin, as it is before God, yet still improperly relating. I am of the opinion that if we follow Kierkegaard on this, everyone is sinning all the time. The plausibility of us actually relating correctly is so small (sure it is possible, but most likely not plausible) that all of humanity is in despair. Specifically those who think they are not in despair are, due to the belief they are properly relating to God, which brings God into the equation enabling sin. Many people will probably disagree with me about this inevitability.

Nevertheless, even if you disagree with what I have just said, the second kind of despair, emotional despair, is one we must be able to enter into. So if you are uncomfortable with delving into the abyss of the first type of despair you can certainly engage this type of despair without sinning. To engage emotional despair is to be fully human, to accept that life is full of ups-and-downs. For in these the good and the bad relate, to some extent, dialectically, as we cannot know good without bad, we cannot understand bad without good. Thus to be human is to experience and participate in the emotions that accompany these circumstances. I think it is timely in Holy Week to consider the occasions Jesus wept, cried out in anguish, experienced the absence of God on the cross. If you believe that Jesus was sinless, yet he experienced these emotions, the emotions cannot be considered sin. So despair this week, allow yourself to plumb the depths of these emotions. Resist the urge to be a facade, acting as if things are great because they are not.

I am reading Paul Tillich today, and came across this: “The vitality that can stand the abyss of meaninglessness is aware of a hidden meaning within the destruction of meaning.” I found it useful for encouraging me to look at the abyss today.

Silas,

ReplyDeleteI can appreciate that quote as I am currently reading Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the whole of which is an attempt to articulate a hidden meaning within the destruction of meaning. It is certainly like staring into an abyss, and it is my goal to be as honest with myself as possible in exploring Nietzsche's arguments. So it seems I am exploring despair, although I don't know which kind. Your distinction between relational and emotional despair, however, is helpful for me. Definitely, emotional despair is not a sin, and is a part of being truly human -- even as Jesus was fully human. I can accept the devotional value of that, especially before Good Friday. And I agree that the type of despair Kierkegaard is describing is a misrelation of the self which is not essentially emotional. So you can be in the midst of joyful, youthful immediacy and still be in despair according to Kierkegaard because you are not resting transparently in the power that established you.

I think we might have to remain in disagreement about the recommendation to sin boldly by engaging in this second type of despair however. It's not the case that I think willfully despairing in the relational sense is wrong because it makes me uncomfortable, or because I suppose that I am "in being myself and wanting to be myself grounded transparently in God." Moreover, the fact that I am almost certainly sinning is not a reason to suppose that what I am doing is not in fact sin, nor is it a justification for willfully pursuing that end. To think that I should sin boldly makes about as much sense to me as saying you ought to do what you ought not to do. If, as Kierkegaard thinks, the Christian conception of sin is of a will opposed to God, and not ignorance of what is good, then to enter willfully into despair would be worse than thinking you are not in despair. But in the end I guess I don't see why I would be forced to choose between these two options. You seem to suggest that, since it is implausible that I am not in despair, then I can either 1) be in despair and pursue it willfully or 2) be in despair unwillingly and pretend that I am not - hide my idolatry. But it seems perfectly feasible to me to be in despair unwillingly and to humbly reflect on and acknowledge my despair. Then at least I would not be guilty of willful sin and I might get closer to having faith in God.

Thanks for the response by the way. This is really a great way to have a meaningful dialectic between Christian brothers and sisters!